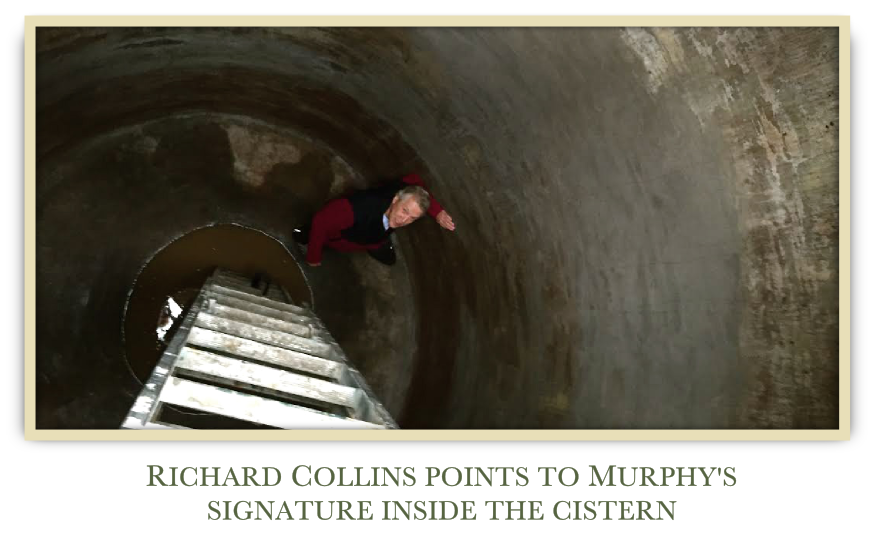

In 1898, a tragedy occurred at the House of the Seasons. James King and his wife, Minnie, had acquired several lots and a home on Friou Street behind the House of the Seasons in 1896. Two years later their two-year-old son fell into a cistern located next to the arbor and, tragically, drowned. Soon afterwards, a 300-pound concrete slab was put on top of the cistern’s opening, where it remained until 2016.

In 1898, a tragedy occurred at the House of the Seasons. James King and his wife, Minnie, had acquired several lots and a home on Friou Street behind the House of the Seasons in 1896. Two years later their two-year-old son fell into a cistern located next to the arbor and, tragically, drowned. Soon afterwards, a 300-pound concrete slab was put on top of the cistern’s opening, where it remained until 2016.

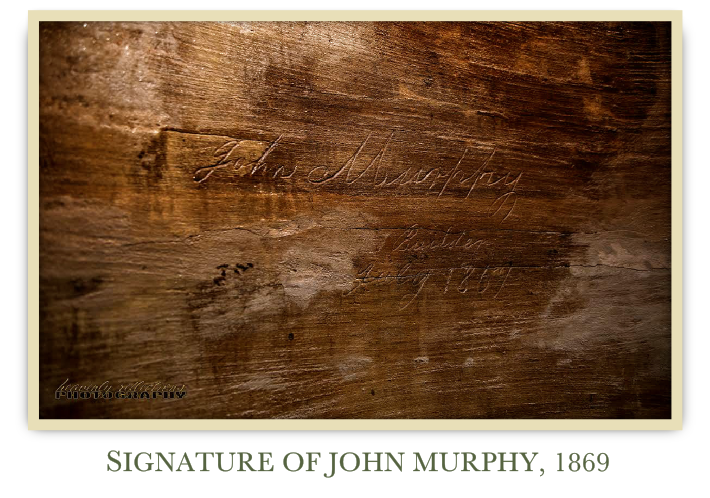

The cistern has a rich history; it was built in the summer of 1869 by John Murphy, a prominent citizen and builder in Jefferson. His signature is located near the floor of the cistern, shown in a photograph below.

The King family had five other children. Their youngest daughter, Frances, married Herbert Liverman of Jefferson, and the couple became good friends with Richard Collins when he purchased the House of the Seasons in 1973. Herbert briefly worked for Richard Collins’ grandfather in the insurance business before having a long successful career with the Southland Life Insurance Company of Dallas.

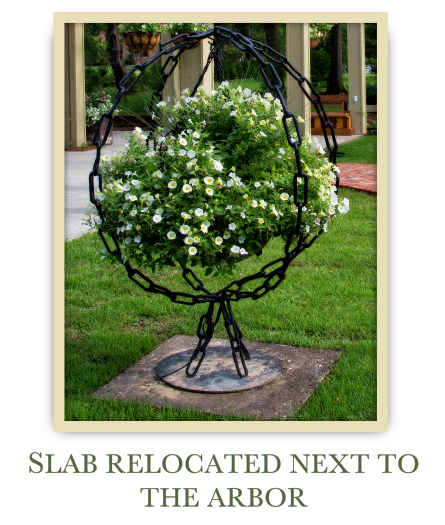

The House of the Seasons acquired the property where the cistern is located in 2014 and moved the slab next to the arbor to serve as the base to a beautiful, chain-circled flower pot where it will continue to be a part of the city’s history.

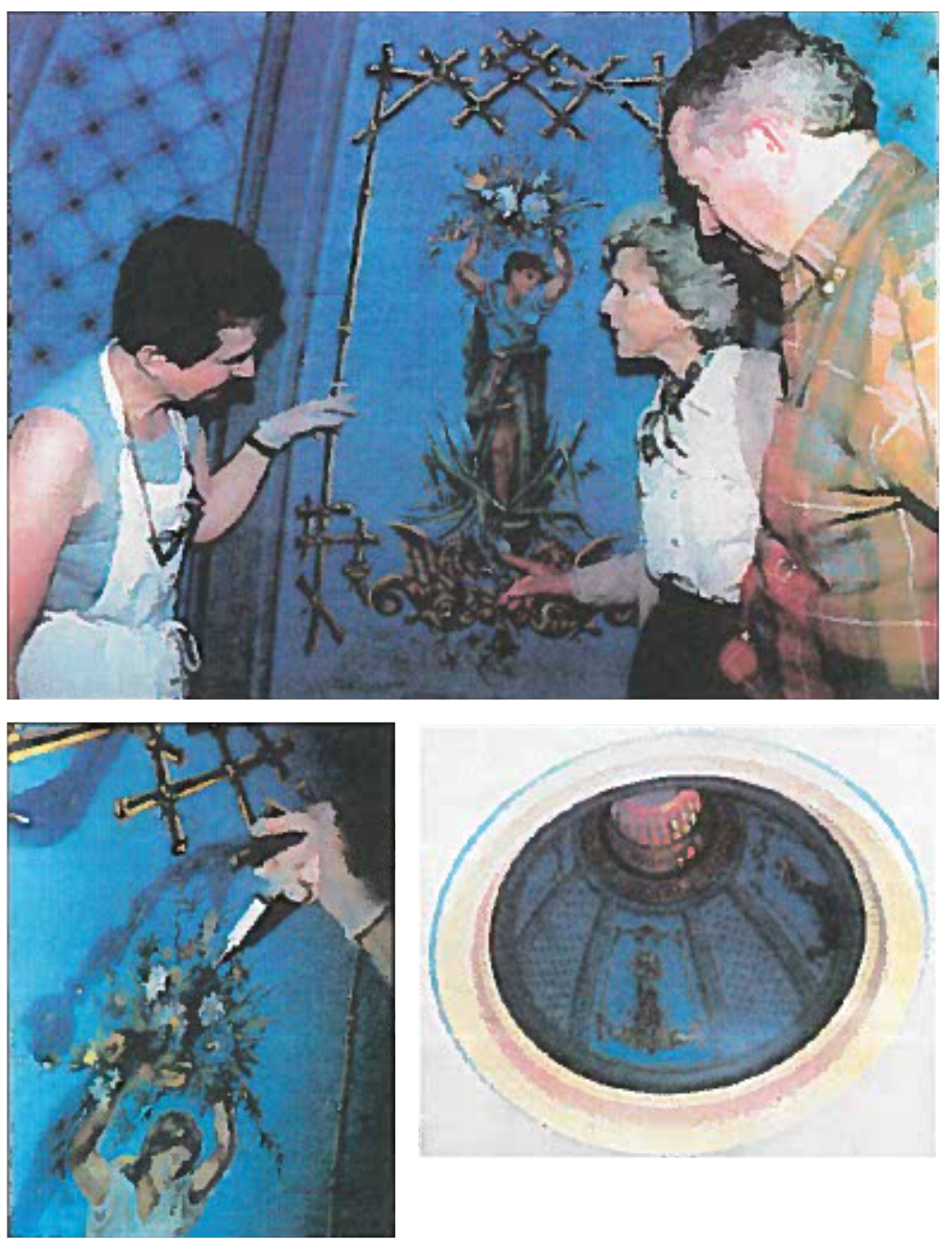

“The dust and dirt was mechanically removed from the bottom of the murals and the wooden base.

“The dust and dirt was mechanically removed from the bottom of the murals and the wooden base. “The fillers in cracks were painted with MSA conservation acrylic paint.

“The fillers in cracks were painted with MSA conservation acrylic paint.

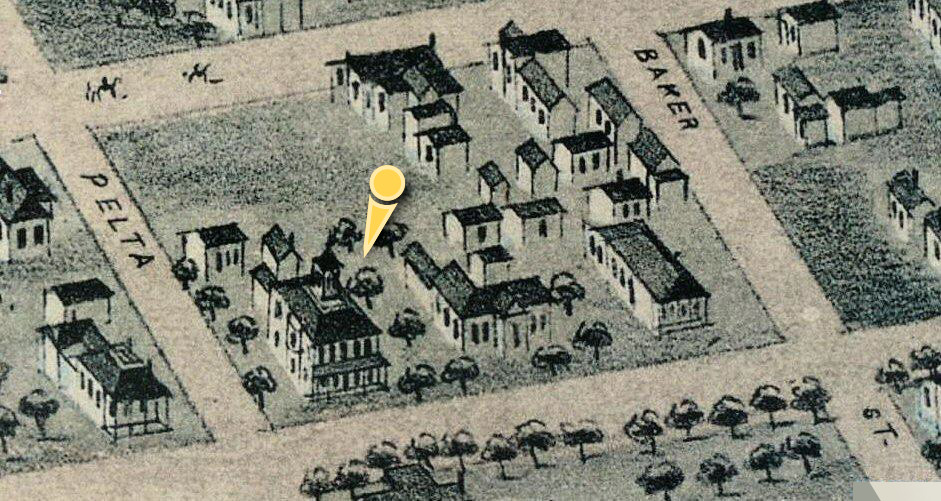

This 1872 Brosius map shows Block P and approximate location of the finds.

This 1872 Brosius map shows Block P and approximate location of the finds.