By Ralph A. Wooster

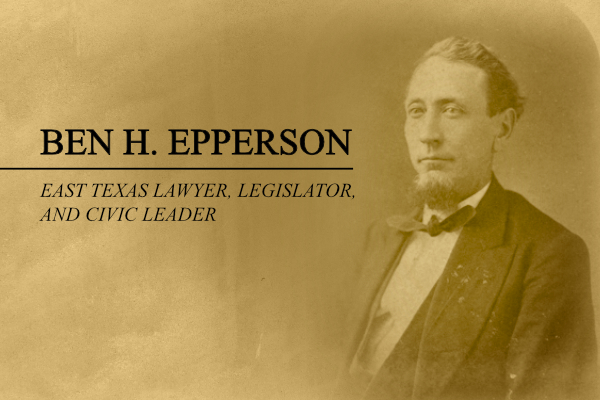

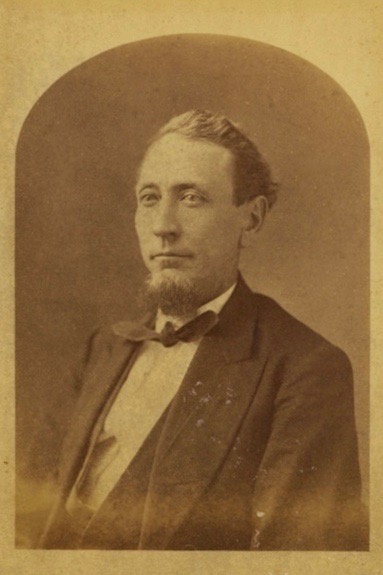

“One of the ablest politicians in Texas,” wrote the editor of the Dallas Herald in April, 1874, in describing the chairman of the judiciary committee of the Texas House of Representatives, Ben H. Epperson of Jefferson.1 Lame in one leg as a result of an accident and forced to support himself with a cane while walking, Epperson had nevertheless played an active role in both politics and business and was regarded by friends and opponents alike as one of the state’s most able legislators. As a candidate for governor, railroad promoter, businessman, and confidant of Sam Houston and James W. Throckmorton, he was in the center of Texas public affairs for over two decades.2

1859

Born in Amite County, Mississippi, in 1826, Epperson came to Texas in the early 1840’s and settled in Clarksville, where he became a law partner of B. H. Martin.3 From the moment of his arrival he was active in civic affairs, and even though under twenty-one years of age was immediately accepted as a community leader. His talents for oratory were quickly recognized, particularly by the Clarksville Standard, which referred to a “Glowing speech” he delivered to Mexican War volunteers, who were being mustered in the town in June, 18464 The following spring he was chosen as a county commissioner to fill a vacancy caused by a resignation, even though he was still under the state legal voting age. In the summer of 1847 he was selected as the Fourth of July orator for the Clarksville Independence Celebration, a traditional event that drew several hundred persons to the Star Hotel5 Already the young Mississippian had established himself as one of the community’s leading public citizens.

In the autumn of 1847, Epperson tried his hand at state politics, seeking election to the House of Representatives as one of the three delegates from Red River and Titus counties. In a five-way contest for local support Epperson trailed both W. B. Stout and J. Gilliam, but picked up a sufficient number of votes to win one of the district’s three seats in the house.6

(Ben & Amanda’s daughter born in 1878)

As a member of the second Texas Legislature, which met from December 13, 1847 through March 20, 1848, Epperson was fairly active, serving on the judiciary, printing and penitentiary committees as well as chairman of select committees on apportionment and fraudulent land grants.7 A firm believer in Texas’ right to the territory around Santa Fe, he sponsored a resolution which protested “against the organization of a separate Government by the authorities of the United States, within the State of Texas”8 The only successful bill introduced by the young East Texas legislator, however, was one compelling owners and renters of cotton gins to keep them enclosed to prevent livestock from consuming excessive amounts of cotton seed.9

After the adjournment of the legislature Epperson returned to Clarksville, where he resumed his law practice. Late in 1849 he was retained by the Chickasaw Indians north of the Red River to represent them in arguing their land claims before the Federal commissioner of Indian Affair. Although Epperson found it necessary to spend several weeks representing his client in Washington, he was ultimately successful in defending the Indian claims and for this success he received the praise of the Chickasaw chiefs.10 Shortly thereafter, however, the lawyer and his clients were at odds over his professional fees, and Epperson severed relations

Chief of the Chickasaw Nation,

1850

with the Chickasaws, writing from Washington to a friend, “I do not expect to do any more business for the Chickasaws or any other Indians. I do not think I would come back here for any price.”11 The severance with his Indian clients was complete and Epperson never again represented them, but his determination to return to the national capital was not so final on many occasions in the next twenty years Epperson would represent clients in Washington.

While his law practice in Clarksville grew in the early 1850’s. Epperson continued to take an active part in public affairs. An admirer of the Kentuckian Henry Clay, Epperson had a deep interest in the development of internal improvements at public expense and in the creation of an efficient system of banking. With these themes as his platform, Epperson assumed leadership of the badly divided and numerically weak Texas Whig party and in the summer of 1851announced as a candidate for governor.12

1842

Epperson had been active in the Whig party since 1848 when he, William B. Ochiltree, Samuel Yerger, and Edward H. Tarrant were electors for the party and the Taylor-Fillmore ticket.13 His announcement as the Whig candidate for governor was the culmination of efforts to develop a real party structure in the state.

With limited funds and only small political support, young Epperson conducted an active campaign for the governorship. Governor Peter H. Bell, an ardent states right Democrat, was an announced candidate for re-election and several other aspirants, all Democrats were also in the field. Among these, L T. Johnson of Rusk, John A. Greer of San Augustine, and T. Jefferson Chambers of Liberty were serious candidates. Connecticut-born E. M. Pease also had some support, but was not a serious contender in 1851. Although various Democratic newspaper lamented the fact that at least four Democratic candidate ere in the contest, thus seriously dividing the strength of that party, the major candidates continued to eek election support throughout the summer months.14

Epperson made a number of speeches during the 1851 campaign. In them he consistently emphasized the need for state aid in the construction of internal improvements. He cited in particular the case of New York State where a resistance to canal building had resulted in economic growth and prosperity.15 At the same time he urged the development of a sound banking system to assist in economic expansion. Although he denied Democratic accusations that he favored an extension of Federal powers, he did speak critically of those who were excessive in their support of state rights. A defender of the compromise measure adopted by Congress in 1850, he condemned nullification talk and ill a speech delivered in Galveston in July, 1851, intimated that Governor Bell was a secessionist.16

The results of the governor’s race must have been disappointing but not altogether surprising to Epperson. The Democratic Party traditionally dominated the state’s elections,17 and 1851 was no exception. Governor Bell was re-elected receiving 13,596 votes, with Democrats Johnson and Greer running second and third, respectively.18 Epperson came in a poor fourth, a few hundred votes ahead of T. Jefferson Chambers. Although he ran well in several East Texas counties, Epperson led only in Grimes and Leon counties. He and John A, Greer tied for the lead in Red River, Epperson’s home county.19

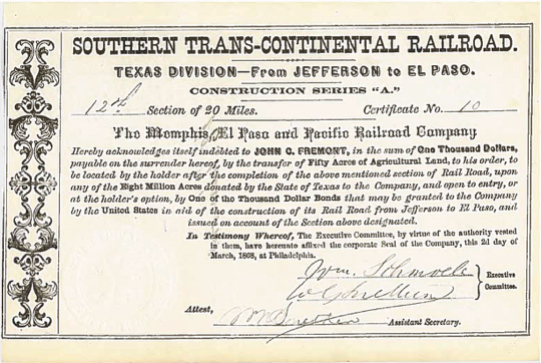

Although badly defeated in the race for governor, Epperson continued to display a keen interest in public affairs. While maintaining his law practice with M. L. Sims, Epperson played an active part in encouraging railroad development. He was a leader in the efforts to build a railroad from Memphis on the Mississippi through northern Texas on to El Paso. On several occasions he served as a member of committees which met with Arkansas leaders to discuss construction of such a road20 He was ever ready to speak in behalf of the proposed railroad, whether it be to a small group in Boston or DeKalb in northeast Texas or to a railroad convention in Memphis.21 So impressive was Epperson in his support for the proposed road that he was appointed chairman of a five-man committee to memorialize the Federal Congress on the subject.

Epperson continued to participate actively in state politics in the mid-1850’s. Like other Texas Whigs he backed Judge William Ochiltree in a spirited but unsuccessful bid for the governorship in 1853.22 And like a number of Texas Whigs he supported the American, or Know Nothing party in the mid-1850’s. Epperson was impressed by the nationalistic planks in the party’s platform and saw the Know Nothing movement as the only hope to halt the growing radicalism of the state Democratic Party.23 Not only did he make speeches for the party in the 1855 elections, but he served as a delegate to the National American Party convention of 1856.24

Following the defeat sustained by Texas Know Nothings in, the 1856 election Epperson returned to his law practice and other business activities. Although he personally supported Sam Houston in his successful bid for the governorship in 1858, Epperson was less active than usual in politics during the period 1857-1858. Continued interest in railroad development result in his becoming a director of the Memphis, El Paso and, Pacific Railroad in the late fifties25 and the acquisition of a sawmill added to his business investments during this period.26 By 1860 he had become one of the wealthiest citizens of the state.27

1855

The increased antagonism between the sections and the growing radicalism in parts of the state constantly troubled Epperson and in 1858 he returned to the political wars with full fury. Considered by now one of the leaders of Texas moderates, Epperson not only campaigned actively for Houston in his effort to defeat Governor Hardin Runnels, but also ran for the legislature himself.28 Although the campaign was a bitter one, both Houston and Epperson were victorious, Houston defeating Runnels 33,375 to 27,500 and Epperson defeating Courtes B. Sutton 433 to 406.29

Houston’s victory over Runnels in the governor’s race encouraged Epperson and other Texas moderates to believe that a new, independent unionist party might be formed, linking together all those who opposed Southern extremism and disunion. Unfortunately for the moderates however, their inability to persuade moderate Democrats, especially Congressman John H. Reagan, to join such a party doomed their efforts.30 The hesitancy of some moderates to leave the regular Democratic party, plus the effect of John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in October, 1859 worked to the advantage of the militant radicals in the state By 1860 public sentiment had turned away from Houston, Epperson, and the other moderates.

Epperson, meanwhile, continued to work for national unity. When a proposal was introduced in the Eighth Legislature instructing Texas delegates in Congress to oppose election of a Republican as Speaker in the National Congress, Epperson unsuccessfully attempted to substitute his own resolution instructing the Texas delegation to “work for national harmony and to lay sectional feeling aside,”31 and when his friend Governor Houston stated that the state of affairs resembled those which existed prior to the American Revolution, Epperson dissented, declaring that the present circumstances were quite dissimilar.32

Though he might occasionally disagree with Governor Houston, Epperson was generally one of his firmest supporters in the legislature and worked to secure his election as either United States Senator or as President of the United States in 1860. As one of Texas’ four delegates to the National Constitutional Union Party convention, Epperson tried to get the party nomination for the hero of San Jacinto and nearly succeeded; Houston coming in second to John Bell of Tennessee.33

Chosen by the Constitutional Union party as a presidential elector, Epperson campaigned vigorously for the Bell-Everett ticket. In late September and October, he stumped the eastern part of the state, speaking at one rally after another in support of the Union ticket. The Clarksville Standard of October 27 reported that Epperson was much encouraged with the prospects of a Union victory and the Dallas Herald of October 31 declared that Epperson’s able speech resulted in warm compliments even from his potential enemies.34 Epperson’s hopes for Union party success in Texas were soon crushed, however, under an avalanche of Democratic votes. John C. Breckinridge, nominee of the Southern wing of the Democratic Party, carried the state by a substantial majority, polling 47,561 votes compared to 15,402 for John Bell and the Constitutional Union party.35

While Breckinridge led in the South, the Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln carried the northern states and with them the election. One by one states of the lower South called special conventions to consider the question of separation from the Union and as momentum for secession grew in Texas, Epperson again found himself with the minority in urging restrain and caution.36

In a special session of to the legislature held in January, 1861, Epperson consistently opposed any movements aimed at taking Texas from the Union, but to no avail. In spite of the opposition of Governor Houston and a vocal minority in the legislature headed by Epperson and John Hancock,37 a state convention was called and in early February approved an ordinance of secession to be submitted to the voters of the state.

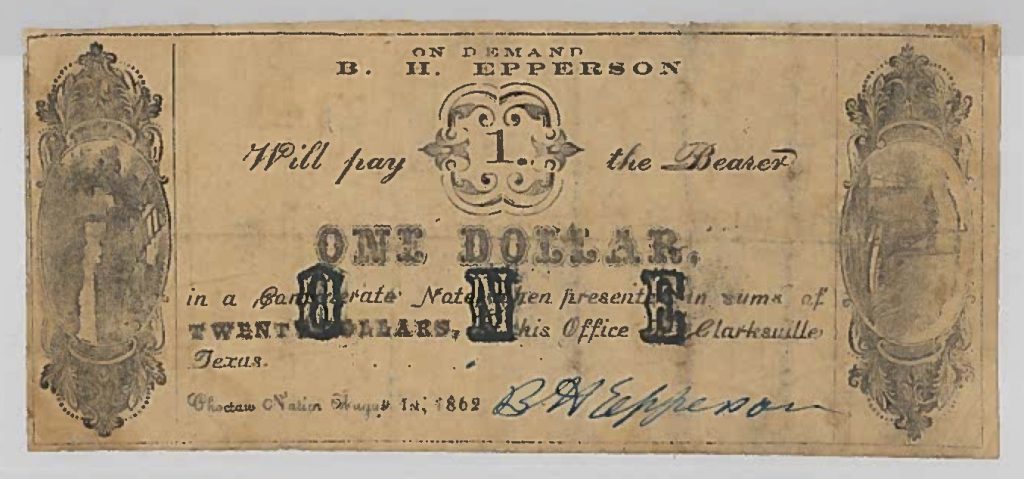

1859

Although Epperson and a small band of other unionists urged their constituents to vote against separation38 as the people of Texas overwhelmingly gave their approval to the secession ordinance passed by the convention and thus severed all ties with the Union. Epperson himself took an oath to support the new Southern Confederacy as required by the state convention,39 but defended Governor Houston when the convention took steps to remove him for failing to take the oath. On the floor of the legislature Epperson moved that

“The Convention now in session in attempting to depose Sam Houston from the office of Governor of the State of Texas, to which position he had been elected by the sufferage [sic] of the freemen of Texas bas undertaken to exercise powers which it was never intended to confer upon it.40”

The secessionists in the legislature quickly countered Epperson’s resolution with a substitute, upholding the right of the convention to subscribe the oath. After brief debate the substitute was passed by a 53-12 count. Epperson again voting with the minority.41 But Houston still defied the convention and refused to take the oath. The convention thereupon passed a unanimous ordinance declaring the office of governor vacant and Houston was deposed.

Shortly before Houston vacated the governor’s office, Epperson was a participant in a conference in which the chief executive informed Epperson, James W. Throckmorton, George W. Paschal, and David B. Culberson that he had received an offer of military assistance from Abraham Lincoln to help keep Texas in the Union. Houston thereupon asked each of the four their advice in the matter. Epperson, youngest of the group, spoke first and favored accepting the offer, but the others opposed on the ground that secession was inevitable. Houston thanked he group and agreed with the majority, declaring that if he were younger he might have accepted Lincoln’s proposition. Then, in dramatic fashion, he threw Lincoln’s letter into the fire.42

1870

Although Epperson continued to feel that the secession convention bad exceeded its powers in failing to submit the Confederate Constitution to the people for their approval,43 he now gave his full support to the The Southern Confederacy. In late April, 1861 be was among a group of prominent East Texans who called for a public meeting “to unite the people in opposition to Lincoln’s policy of coercion.44 In June he was chairman of a Red River County meeting devoted to raising fund to support a military company,45 and in July he was among those East Texans who agreed to contribute a portion of their crops to the confederacy.46

In the fall of 1861 Epperson retuned to the political wars, announcing his candidacy for a seat in the Confederate Congress, Admitting that he had earlier opposed secession, he declared that he now regarded separation as final and perpetual. In his announcement for office he stressed the need for southern unity outlining his platform “of peace among ourselves, oblivion of party division, obliteration of past party discord, and prosecution of the war with united energy.47

The campaign for the congressional seat from the sixth Texas district was heated. In addition to Epperson, other announced candidates were W. B. Wright, T. J. Rogers, and B. H. Ward. Throughout late September and early October the candidates stumped the district, discussing their program and policies. On many occasion all four appeared on the same platform and pleaded their cause.48 Epperson was particularly vulnerable to the charges that he had opposed secession. The Paris Advocate was especially bitter in its attack upon Epperson, describing him “an unconditional submissionist to Mr. Lincoln’s administration, and entirely unreliable in the great issue of the day.49

The race developed into a two-way contest between Epperson and W. B. Wright, as the other two candidates trailed far behind. Epperson showed great strength in his own Red River County, polling twice a many votes as his three opponents,50 but did less well in other counties of the district. In these counties Wright pulled steadily ahead and defeated Epperson by over 300 votes, The official returns showed Wright with 3,144 votes, Epperson 2,777, Rogers 537. and Ward 256.51 Unquestionably, the charge labeling Epperson a “submissionist” had hurt in his bid for a seat in the Confederate Congress.

Following his defeat in the congressional race, Epperson turned to his Jaw practice in Clarksville and for the next four year played no active role in political affairs.52 His lame leg prevented any military service but he generously contributed funds and supplies to the war effort. Occasionally he offered some support to candidates seeking state or local office53 but in the main he was politically inactive during the war. His long interest in transportational development continued to take much of his time as be worked to promote the Memphis and EI Paso Railroad. The state had chartered the proposed road in 1853 and had given a generous land grant of 10,240 acres to the mile but the difficulty in obtaining sufficient capital had delayed construction work before the war and now during the war the difficulty of obtaining building materials prevented much additional construction.54

The end of the war in the late spring of 1865 brought Epperson back into public life. The hope of obtaining Eastern financial backing for the Memphis, El Paso, and Pacific Railroad took him to Washington and New York several times in late 1866 and 1866.55 In May, 1866, he was chosen as president of the company and as a consequence was required to spend more and more of his time in behalf of the railroad.56 The political uncertainties of the Reconstruction period, however made potential investors cautious and as a result little tangible improvement of the company’s financial structure was for the moment possible.57

As President Johnson’s plan for reconstructing the southern states unfolded in late 1865 and early 1866, more and more of Epperson’s friends pleaded that he enter the 1866 elections as a candidate for either govern or lieutenant governor. The principal candidates in the field were two friends of Epperson’s, James W. Throckmorton and Elisha M. Pease. Like Epperson, both had been opponents of secession in 1861, but Throckmorton had served as a brigadier-general in the confederate army and thus was acceptable to southern conservatives, whereas Pease, who had been silent during the war \vas considered the candidate of the former Texas unionists and radicals. Epperson now found himself faced with a personal decision. One of his friends had already entered his name in the governor’s race, while others entered his name lieutenant governor on the Pease ticket. Throckmorton, his friend of many political battles, was pressing Epperson to throw support to his camp.

1870

In late April, 1866, Epperson wrote to J. W. Thomas, editor of the Paris Press announcing his withdrawal from both the governor’s and lieutenant governor’s races. Declaring that he could not believe that Pease was a Radical as many had charged or that Throckmorton wished to renew the war as others had claimed, Epperson stated that he had “no heart for political strife” and did not wish “to awaken old party discord.” He pleaded with the people of Texas that they forget the old arguments over secession. “Let us make no man’s position upon secession a text for political preferment,” he stated. “The primary object of every man who really desires the good of his country, is the restoration of peace, of property and of constitutional liberty”58

Epperson’s withdrawal from the race left the field to Throckmorton and Pease, and in the ensuing contest Throckmorton, the conservative candidate, won an easy victory over Pease 49,277 votes to 12,168.59

1874

With Throckmorton’s election in the summer of 1866, civil government was restored in Texas. Epperson, like many former Whigs now a conservative Democrat was active in various party functions that summer, serving as chairman of the resolutions committee at the state convention in July and a delegate to a national convention held in Philadelphia in August. His support of Johnson’s plan for reconstruction gained him praise throughout the state and gratitude from the President who, according to one editor, regarded Epperson as “one of the most influential of the many prominent men in the Country who are laboring honestly to restore harmony and good feeling between the two sections.60

Epperson’s name was prominently mentioned when the state legislature turned to choosing the first United States Senators from Texas after the war. His name was placed in nomination in the early voting and (or several ballots he and Judge O. M. Roberts, who had presided over the secession convention in 1861, were the main contestants as Senator from the eastern part of the state. Finally, on the 24th ballot Roberts was elected, receiving 61 votes to 49 for Epperson.61 David G. Burnet, former president of the Texas Republic was chosen as Senator from the western part of the state.

The defeat in the Senate race only whetted Epperson’ appetite for political battle an in the fall he announced as a candidate for the United States Congress. The old charge of not supporting the Confederacy were once again brought up, but answered successfully by Epperson’s friends. Although there were three opposition candidate in the field, Epperson’s victory was never in doubt as be carried the district by an overwhelming majority.62 Thus once again Epperson was back in political office and once again he journeyed to the nation’s capital.

Although chosen to represent Texas in Washington Epperson and his colleagues. Senators Burnet and Roberts and Representatives George W. Chilton and A. M. Branch, were never permitted to take their seats in Congress. The radical-controlled Congress set up a committee to investigate the claims of all southern congressmen and in the next few month wrested control over reconstruction from President Johnson and imposed new restrictions on the former Confederate States.

Epperson himself waited for some days in Washington, but when he saw that Congress had no intention of seating the Texas delegation turned to business matters. The financially hard-pressed Memphis, El Paso, and Pacific Railroad was seeking Eastern backing and Epperson moved back and forth between the capital and New York City, trying on one hand to attract Eastern inventors and on the other to keep informed on political matters. Conferences with other members of the Texas delegation, secretary of State William S. Ward, and President Johnson indicated, however, that little progress was to be expected on the political front.63

1875

In late December members of the Texas delegation, discouraged over the failure of Congress to seat them, issued an address t the Congress and people of the United States. Written by Judge Roberts but with Epperson’s full advice and counsel, the address called for an end to sectional bitterness and pleaded for recognition that the people of Texas were loyal to the government of the United States.64

Following the publication of their address most of the Texas delegation returned home, but Epperson stayed behind on business matters. The well-known adventurer and railroad investor, John C. Fremont, had become interested in the Memphis, El Paso, and Pacific and Epperson was eager bring him into the venture.65

For the next three years Epperson’s main energies were devoted to railroad business. Although he served as a delegate to the National Democratic Convention in 1968,66 his movements in the late 1860’s were largely in behalf of the railroad.67 The sale of half of the stock of the company to Fremont in the late sixties meant that control of the Memphis and El Paso would eventually pas to other hands, but for the moment Epperson continued to direct the company as president. By 1869 construction was well under way and Epperson appealed to property owners along the proposed route to exchange their land for stock in the company.68 By early 1870 over 100 miles of track were laid and Epperson reported to the public that the picture looked bright.69

The need for additional capital continued to haunt the directors of the Memphis and El Paso. Fremont played more and more an active role in company operations and in 1870 supplanted Epperson as president. Under Fremont’s control, expenditures and indebtedness rose rapidly and although the legislature continued to give some financial assistance the road was eventually bankrupt. In 1872 its assets were taken over by the Texas Pacific Railroad and the track constructed became a part of that vast system.70

As Epperson gradually played a smaller role in the affairs of the dying Memphis and El Paso he found additional time for politics. In 1870 he had moved to the town of Jefferson in Marion County and at the request of friends was a successful candidate for the state legislature in the fall of 1873. Thu in January 1874, Epperson was once again in Austin serving in the House of Representatives, a position he had first held some twenty-five years earlier.

1874

The Fourteenth Texas Legislature, meeting in regular session from January 13 to May 4, 1874 and in special session from January 12 to March 15, 1875, devoted much time to the question of a new state constitution. Epperson, who was a member of the house committee on constitutional amendments, agreed that a new document was necessary but opposed the bill providing for a convention to draft the document.71 Questioning the legality of legislative action in this respect, Epperson spoke out strongly against the convention bill, but once again found himself a member of the minority as a majority pushed the measure through the legislature.72

Following the adjournment of the legislature in 1876, Epperson returned to his law practice in Jefferson. He continued to be a popular speaker and was asked repeatedly to address civic and political gatherings in East Texas. In the fall of 1875 he was selected as a delegate to a railroad convention to be held in St. Louis and in late November journeyed to that city, where he served with his friend James Throckmorton as a member of the Texas delegation.73 Highly respected and praised by friend and foe alike, Epperson was by now regarded as one of the senior leaders of the State Democratic party. There were rumors that he would be a candidate for governor in 1876 but Epperson himself showed little interest and was content to serve as one of the party’s presidential electors that year.74

Although only in his early fifties, Epperson curtailed his public activities considerably in 1877 due to failing health. The year of public service and expanding professional and business obligations had taken their toll, however, and in September, 1878, Epperson died from nervous prostration brought about by excessive work. Twice married, he left a widow and five children.75 Pioneer railroad builder, lawyer, legislator, and civic leader Epperson had devoted over thirty years to the economic growth and political stability of his region, his state, and his nation. His had been truly a life of public service.

NOTES

1 Dallas Herald, April 18, 1874. Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the Research Committee of Lamar State College of Technology.

2 There are brief biographical sketches of Epperson in Walter P. Webb, Handbook of Texas (2 vols., Austin, 1952), I, 568-569, and in the Epperson Papers located in the Archives of the university of Texas Library.

3 Ibid.; Clarksville Northern Standard, January 15, April 8 184, The Journal of the House of Representatives, Eighth Legislature, State of Texas (Austin, 1860), 726, gives his date of migration to Texas as 1841 but this may be a little early. Epperson had attended Princeton before coming to Texas, but left before graduation.

4 Clarksville Northern Standard, June 23, 1846.

5 Ibid., June 23, July 10, 1847.

6 Ibid., September 11, November 13, and December 4, 1847.

7 Journals 01 the House of Representatives of the State of Texas (Houston, 1848), 13-14, 67, 361-365, 445-447, 513. For more on Epperson’s role in the apportionment controversy see Ben H. Procter, Not Without Honor: The Life of John H. Reagan (Austin, 1962) 68-69.

8 Ibid., 690, 817.

9 Ibid., 239, 543.

10 Epperson to Thomas Ewing, December 10, 1849; Chickasaw Chiefs to Orlando Brown, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 11, 1850; Orlando Brown to Epperson, March 27, 1850, in Epperson Papers, Archives of the University of Texas Library.

11 Epperson to Cyrus Harris, April 23, 1851 Epperson Papers.

12 Clarksville Standard, June 18, 1851.

13 Galveston Weekly News, October 13, 1848. The Democratic party carried the state in 1848, Lewis Cass receiving 11,644 votes compared to 5,281 for the Whig ticket. W. Dean Burnham, Presidential Ballots, 1836-1892 (Baltimore, 1955), 764.

14 Clarksville Standard, June 14, 1851, July 19, 1851; Galveston Weekly News, June 17, 1851.

15 Clarksville Standard, June 21, 185l. ,

16 Galveston Weekly News, July 22, 1851.

17 In the four national elections in which Texas participated prior to the Civil War the Democratic party was always victorious. Only one Texas county, Bandera, as carried by the opposition (non-Democratic) in two national elections during the period. Ten other counties were carried by the opposition in one national election in the ante-bellum period; all other Texas counties were carried by the Democratic Party in every election. See Burnham, Presidential Ballots, 1836-1892, 764-810.

18 E. W. Winkler, Platforms of Political Parties in Texas (Bulletin of the University of Texas, 1916) , 644. There are incomplete return in Clarksville Standard December 6, 1851; Telegraph and Texas Register, September 6, 1851; and Texas State Gazette, September 6, 1851.

19 Outside of the three named counties, Epperson’s greatest strength was in Lamar Harrison, and Cass Counties. He was a strong second in two populous coastal counties, Harris and Galveston. He ran very poorly, however in Central and West Texas.

20 See Clarksville Standard, March 13, 1852, June 9, 1855, March 5, 1859.

21 Ibid., March 13, 1852, July 7, 1855, March 5, 1859. The Memphis Eagle quoted in the Clarksville Standard, March 5, 1859, declared that Epperson made “a spirited and effective speech” to the railroad convention.

22 Ochiltree ran second in a contest with five Democrats, trailing only successful candidate, Elisha M. Pease of Brazoria County. Winkler, Platforms of Political Parties in Texas, 644; Texas State Gazette, August 27, 1853.

23 The platform of the Texas Know Nothings called for the “preservation and perpetuation of the constitution and the Federal Union as the bulwark of our liberties” and announced “opposition to the formation or encouragement of sectional and geographical parties.” Winkler, Platforms of Political Parties in Texas, 69. See also Frank H. Smyrl, “Unionism in Texas, 1866-1861,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, LXVIII (October, 1964), 172-195.

24 Clarksville Standard, August 5, 1855, October 26, 1856; Llerena Friend, Sam Houston: The Great Designer (Austin, 1954) I 294.

25 Dallas Herald, November 7, 1860.

26 The manuscript returns of the Industrial Schedule for the Eighth U. S. Census for Red River County, 1860, show Epperson with a capital investment of $10,000 in the sawmill. He employed eight laborers and had an annual production valued by the enumerator at $7,500.

27 A study of the manuscript returns of Schedule No.1, Free Inhabitants, of the Eighth U. S. Census shows that 263 Texans had 100,000 or more in total property. Epperson was listed with $60,000 in real and $40,000 in personal property and thus belonged in this category of wealthy Texans.

28 B.H. Epperson to James W. Throckmorton, June 28, 1859, Epperson Papers, The University of Texas; Clarksville Standard, July 16, 1859. See also Friend, Sam Houston 312-313.

29 Clarksville Standard, August 18, 1859. For the statewide race between Houston and Runnels see Friend, Sam Houston, 323-325, and Francis R. Lubbock, Six Decades in Texas (Austin, 1900), 247-254.

30 See Procter, Not Without Honor, 112-113. Epperson, himself, was never completely convinced that Reagan was truly a unionist. See James W. Throckmorton to Epperson, August 18, 1859, and September 13, 1859, Epperson Papers, The University of Texas. In one of these letters Throckmorton admonishes Epperson “you have no charity for Reagan whatever.”

31 Journal of the House of Representatives, Eighth Legislature, State of Texas (Austin, 1860), 347.

32 Ibid., 93-94.

33 Mural Halstead, Caucuses of 1860: A History of the National Political Convention of the Current Presidential Campaign (Columbus, 1860), 104- 105; Smyrl, “Unionism in Texas, 1850-1861,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, LXVIII, 176-177.

34 The Constitutional Union Party’s campaign in Texas is ably discussed by Frank Smyrl, “Unionism in Texas, 1856-1861,” Ibid., 177-185.

35 Burnham, Presidential Ballots, 1886-1892, 764

36 ln a mass meeting in Paris on December 15, Epperson was one of the speakers who unsuccessfully opposed adoption of a resolution condemning Northern aggression against the South. Clarksville Standard, December 22, 1860.

37 On January 23, Epperson voted with a fifteen-man minority that opposed offering the hall of the House of Representatives to the convention for use in its sessions. Epperson later voted with a thirteen-man minority against approving the work of the secession convention. Journal of the House of Representatives of State of Texas, Extra Session of the Eighth Legislature (Austin, 1861), 45, 58-61. See also Clarksville Standard, February 2, 1861.

38 Epperson was one of the signe.rs of an “Address to the People of Texas,” issued by unionist members of the legislature and convention in an attempt to convince Texas to reject secession. Smyrl, “Unionism in Texas, 1856- 1861, Southwestern. Historical Quarterly, LXVIII, 191.

39 Journal of the Adjourned Session [of the Eighth Legislature] (Austin, 1861), 126.

40 Ibid., 133.

41 Ibid., 133-134; Clarksville Standard, April 6, 1861

42 George W. Paschal, “The Last Years of Sam Houston,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, XXXII (1865-66), 633; Charles A. Culberson, “General Sam Houston and Secession,” Scribner’s Magazine. XXXIX (1906), 586-587; Friend, Sam Houston, 345-346; Claude Elliott, Leathercoat: The Life History of a Texas Patriot (San Antonio, 1938), 59.

43 See Clarksville Standard, March 30, 1861, April 27, 1861.

44 Ibid., April 27, 1861.

45 Ibid., June 15 1861.

46Ibid., July 20, 1861. Epperson pledged to contribute 100 bales of cotton to the Confederate government.

47 Ibid., September 28, 1861.

48 Ibid., October 12, 1861, lists eleven speaking engagements for the candidates in late September and early October.

49 News items, Paris Advocate, quoted Dallas Herald, October 30, 1861.

50 Epperson received 475 votes in Red River County, Wright 197. Rogers 5, and Ward 6. Clarksville Standard. November 23, 1861.

51 Dallas Herald. January 2, 1862. Various county returns are given in November 16, 1861, and the Herald, November 13, November 20, 1861.

52 Alexander H. Stephens in his Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States (2 vols.; Philadelphia., 1868-1870), II, 761, refers to Epperson as a member of the Confederate Congress but this appears to be an error. Epperson is listed in none of the Journals of the Confederate Congress.

53 See James H. Bell to Epperson, April 13, 1864; James W. Throckmorton to Epperson, June 18, 1864, Epperson Papers, University of Texas; and Elliott, Leathercoat: The Life History of a Texas Patriot, 65.

54 See Andrew Forest Muir, “The Thirty-Second Parallel Pacific Railroad in Texas to 1872,” unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Texas, 1949, p. 197; and Albert V. House, Jr., “Post-Civil War Precedents for Recent Railroad Reorganization,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XXV (March, 1929), 509-510.

55 Dallas Herald, November 25. 1865. August 4, 1866.

56 lbid.

57 Epperson’s Account Book, 1859-1871, in the Epperson Papers, University of Texas, is filled with materials relating to the Memphis, EI Paso, and Pacific. See also Muir, “The Thirty-Second Parallel Pacific Railroad” 197-217.

58 Epperson’s letter was widely reprinted. See Dallas Herald, May 17, 1866; and Texas Republican, May 19, 1866.

59 Charles W. Ramsdell, Reconstruction in Texas (New York, 1910), 108-112.

60Dallas Herald, August 18, 1866. See also Dallas Herald, July 18, 1866. August 4, 1866, August 11, 1866.

61 lbid., September 1, 1866.

62 Ibid., October 6, 1866, October 20, 1866, November 3, 1866.

63 Epperson’s role in this period is ably described in O.M. Roberts, The Experiences of an Unrecognized Senator,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly. XII (October, 1908), 97-106.

64 The address may be seen in Roberts, “The Experiences of an Unrecognized Senator,” 106-119, and in the Dallas Herald , February 2, 1867.

65 The political situation in Washington continued to look leak and Epperson reported to Texas that “political matters are in a wild state here.” Dallas Herald, February 2 1867.

66 Dallas Herald, May 30, 1868.

67 Ibid., May 4, 186’7, December 21, 1867, June 19, 1869.

68 Ibid. October 9, 1869, November 6, 1869.

69 Ibid., February 3, 1870.

70 The story of the financial involvements of the Memphis and EI Paso is an involved one. For full details see Muir, “The Thirty-Second Parallel Pacific Railroad in Texas to 1872,” 199-217; House, “Post-Civil War Precedents for Recent Railroad Reorganization,” 509-522; and Allen Nevins, Fremont: The West’s Greatest Adventurer (2 vols.; New York, 1928). Vol. II, 674-687.

71 Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Texas: During the Session of the Fourteenth Legislature . . . (Austin, 1874), 95; Dallas Herald, February 21, 1874

72 See Dallas Herald, February 13, February 27, and March 13, 1875.

73 Ibid., December 4.. 1875. Among those present at the meeting were Jefferson Davis, Joseph E . Johnston, William T. Sherman, and P. G. T. Beauregard.

74 Ibid., January 8, 1876.

75 Biographical sketch in Epperson Papers, The University of Texas; Handbook of Texas, I, 569.